Seasoned Fortune 500 companies have a deep understanding and appreciation for marketing. Coca-Cola may already one of the most recognized brands in the world, but they nevertheless spend billions of dollars every year on their marketing efforts. (And you can bet they’re not doing it on a whim. They know exactly what those dollars will bring them in return.)

On the other side of the spectrum, startups and micro-businesses view marketing as a matter of survival, not theory: their business will disappear if they don’t invest in it.

Between those two extremes, however, an interesting thing often happens: companies forget about marketing. Once a company gets past a few million dollars in revenue, it’s tempting to let things slide. Some of these companies stop marketing altogether.

Business is growing and everyone’s staying busy, they think, so why bother with the expense and hassle?

I’ll tell you why.

Marketing is food, not medicine

Inexperienced companies regard marketing as medicine to be taken when something is wrong. (“Not enough customers? Take some marketing and call me in the morning.”)

This is completely wrong-headed thinking, and it’s one of the reasons so many otherwise successful businesses wind up failing. They get used to feeling busy…until they realize it’s too late to start what they should have been doing all along.

Marketing is food. It’s the regular, sustained nourishment that gets your business where you want it—and keeps it there. You need it throughout the day, every day.

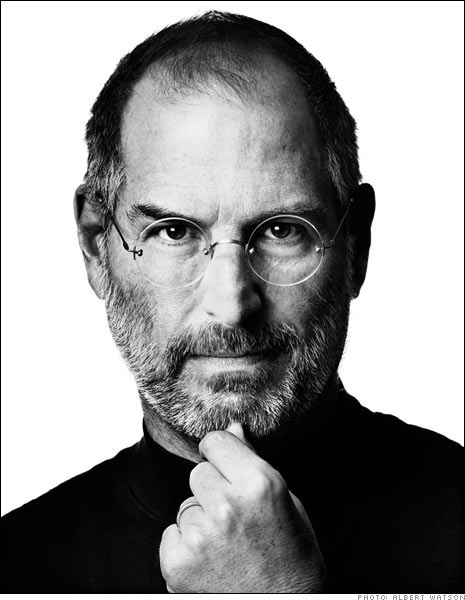

Peter Drucker, one of the leading experts on management theory, wrote:

Because the purpose of business is to create a customer, the business enterprise has two—and only two—basic functions: marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs.

He also wrote:

Marketing is not only much broader than selling; it is not a specialized activity at all. It encompasses the entire business. It is the whole business seen from the point of view of its final result, that is from the customer’s point of view. Concern and responsibility for marketing must therefore permeate all areas of the enterprise.

This perspective is what keeps Fortune 500 companies so intense about sustained, well-funded marketing—even when they’re already successful by any measure.

While inexperienced businesses wait until they’re starving to start looking for nourishment, these savvy enterprises eat regular, healthy meals throughout the day, keeping them strong and thriving year after year.

Successful companies never stop marketing

Here are four common-sense reasons why the most successful companies in the world engage in vigorous, ongoing marketing efforts:

Ongoing marketing prevents “reputation rot”: If you surveyed everyone who’s heard about your company, you’d probably find that their understanding of who you are and what you do is out of date by at least a few years. Your company is constantly improving, but people’s perceptions tend to remain fixed. Every year that passes brings them further and further out of sync, until hardly anyone actually understands what your company has become. It takes years to shape and define your reputation, so you need to be doing it all the time. You can’t wait until it’s hopelessly out of sync, and only then start the arduous process of convincing everyone you’ve changed. (If you do, you’ll never make it to the other side.)

Ongoing marketing shapes your customer base: As your company evolves, your company will need to target different audiences. Sometimes your focus changes only slightly, and other times you have to start with a completely new customer base. Either way, you need to be constantly evaluating your target and adjusting your messaging, visuals, and strategy according.

Ongoing marketing gives you lots of options: Having “just enough” business isn’t enough. If you’re actively marketing, there should always be more demand for your offering than you can actually meet. This gives you the option to pick and choose your customers, to focus on the most profitable (or most enjoyable) ones, and to have a waiting list ready for when times get slower.

Ongoing marketing secures your company’s future: The single most important reason for engaging in active, ongoing marketing is simply that it secures your company’s future. Marketing creates business. You may have lots going on right now, but will it still be there in six months? A year? Three years? Savvy business owners don’t leave their future up to chance; they’re planting seeds now they can harvest next season.

If your company currently has lots of work, happy customers, and a busy staff, then you’ve successfully achieved a key milestone in the life of a business: viability. This isn’t the end of your journey, though, but the beginning — and marketing will be your constant companion at every step you take from here on out.